Twenty-three years after the release of Young and Dangerous 古惑仔, photographer Issac Lam—who isn’t much older than the film—is recreating its spirit in a photoshoot.

“We’re trying to take the old-school 古惑仔 elements for styling, and imagine what a modern 古惑仔 may look like—wearing Crocs,” he says.

Issac isn’t just interested in retro looks. He’s hoping to restore an elusive attitude that once permeated Hong Kong culture: when young people were unafraid to show their true selves. “If you look at old interviews of Beyond, Leslie Cheung, Maggie Cheung, it was fine to drink and chill during interviews,” he says. “Artists would smoke in front of the camera. Even City Magazine used to have nudes.”

For the twenty-five-year-old photographer, the nineties were a realer time: pockmarked with charming flaws, before the dawn of digitalisation, before Hong Kong mass culture slipped into a death spiral of conservatism, censorship, and unoriginal KOLs. “I don’t see people daring to do anything anymore,” he says.

Originally a student of fashion design and branding, Issac’s journey to photography started from a desire to make a cultural statement. “I felt like design couldn’t let me express what I wanted. A piece of clothing, it goes by seasons— whereas with a photograph, I can take a picture today, and tomorrow I can say something.”

The choice seems to have paid off: in his first three years of work he’s gained a reputation as one of Hong Kong’s most innovative young fashion photographers, amassing a list of clients and features local (City Magazine, Jet, Ming Pao, Lane Crawford) and international (Adidas, Nike, and Vogue).

Issac’s personal work is a direct response to the conventions of mass-market fashion photography. “Fashion talks about people’s desires—is it really this limited?” he asks. “I feel like fashion photography can contain a lot more.”

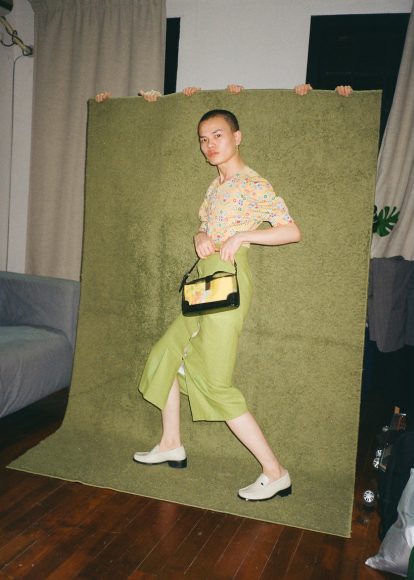

In fashion, models are often treated as rigid templates for a designer’s work. But in Issac’s photos the clothes are a substrate for an intimate dialogue between model and photographer, exploring appearance and identity in what Issac calls “aesthetic play.” His models, mostly young and thin, wouldn’t draw special attention if encountered on the street. They appear to be ordinary people—recast as the stars of an enchanting parallel universe.

The outfits are spectacular: invariably maximalist, draping wildly or chopped short. Issac brings his subjects into a skilled choreography with the costumes, willing them into dramatic and indefinable poses. His most memorable photographs rebel against the limits of gender, revealing a sensuality that feels free and instinctive. The result is something that suggests the limitless possibilities of at least certain types of bodies.

It’s important that Hong Kong people feature prominently in his work—“I don’t look for European models because I feel like there are so many,” he says. “I don’t have to help them say ‘this is beautiful’ or be even more perfect.”

For Issac, “beauty” and “ugliness” are not organising principles, but merely waypoints towards more interesting ideas. One of his recent fixations is the idea of “tackiness”: in one series, Issac photographs a model dressed in metallic gold—a riff on the gauche taste of the nouveau riche—and in the next series, a model holding a handheld plastic fan. “[The fan] is tacky, but functional. It’s representing the culture here,” he says. “You won’t see foreigners holding this fan.”

That may be why the work feels both revelatory and familiar. Issac describes how a friend visiting the city remarked on Hong Kong’s moisture. “Wet, he said. Even the ground is full of puddles. Maybe this Hong Kong is more interesting to him, but we are too used to it. So I want to bring out these elements and make people notice them. It’s just a reminder of: hey, these things are around.”

In this way, Issac’s pictures of models and misfits honour a Hong Kong youth culture that’s hidden in plain sight. For us, these are opportunities for self-recognition and create the possibility for subsequent transformation. They insist that there is more to being here, and being young, than what our eyes can see. They remind us that we can be fearless.

Originally published in the Still / Loud magazine in February 2019. Republished online in March 2020. Kylie Lee and Michael Chiu contributed reporting; Kaitlin Chan contributed editing.