Sheung Yiu is one of Hong Kong’s most interesting conceptual photographers, though of course, he would never say that. “Sometimes I think my work doesn’t matter,” he says, and admits even his parents don’t fully get what he’s trying to do. That may not be their fault. The self-taught 26-year-old — who also goes by Kenneth — is as much an artist as a philosopher: his deceptively whimsical pictures are records of his thorough, often demanding investigations into the nature of images.

Sheung Yiu makes work that is playful yet systematic, pleasurable yet challenging. In his award-winning series “(PHOTO)graphy”, he contorts images into themselves, manipulating color, texture, and flatness, to expose the peculiar way the medium mimics the world. His latest project “Look Like Science” builds on this approach, revealing the often half-truthful way photography describes things we accept as scientific fact. Can thinking about photography help us understand the way we think about science, and hence, the way we think about reality?

A photograph by Sheung Yiu often contains a stroke of deadpan humor (his first project was literally a dick joke). But each punch line — and sometimes it is subtle — invariably includes an insight into visual thinking. Working backwards from the punch line, you can deconstruct the picture to understand its underlying concerns. Sheung Yiu is like a teacher who shows you the answer, then asks you to figure out the question.

Still / Loud has the honour of calling Sheung Yiu a contributor and a friend. We interviewed him shortly before he left to pursue an MFA at Aalto University in Finland—what started as a quick chat in McDonald’s turned into a discussion about images, beauty, science, and truth.

/

Still / Loud: Tell us about how you started making photographs.

Sheung Yiu: I went to a city called Figueres—that’s Salvador Dali’s birthplace—and I went to some museums and really liked surrealism. So my first photographs were surrealist still lifes. I used things that were in my dorm or things I got from the supermarket. Like two avocados and then some penne pasta—avocado comes from the Aztec word for testicle, and penne is like [the Italian word for penis] pene—and I somehow made them into a composition.

But I didn’t explain to people the meaning; I just thought the process was interesting. Like, you could hide a message inside the photograph, but when you show someone, they might not know it’s there.

Photography is an enigma. The attractive thing about it is that it can’t completely convey your thoughts.

You worked in commercial photography, but you didn’t like it.

When I was a commercial photography assistant, I learned how things like, what’s a portrait, what’s lighting. I still feel grateful to the people I met those days. But I never thought I would be a commercial photographer. I feel like commercial photography is about being impressive. And in that environment you have to be really fast. I can’t bear that pressure, getting chur-ed by people.

My photography is very slow. I might have to think for a month before I know what I want to do.

In commercial photography, you’re showing people the surface level. If you were learning calligraphy, and you ask, why do you draw that dot that way, or why do you use this kind of ink, these things are not interesting questions. It’s missing the point.

Even if you look at the history of painting, in the Renaissance, artists really emphasised realism. They studied perspectives and compositions while contemporary artists have a different entry point. They play with surface, framing, color, they experiment with gesture and motion. It gets to a point where paintings became very abstract.

When an art slowly evolves, it will get to a very meta state. It’s not just about considering the technical aspects or the appearance, but what’s the essence of the medium? Photography’s essence—is it about reality and falseness? Is it a lie? Or are photographs like a photogram, just light and composition, completely abstract and has nothing to do with what you were photographing?

When did you start seeing things this way?

It’s hard to say. When I started making work, I wanted to do something that didn’t have to do with appearance or the look of something. As I made more work I started to understand what kind of photographer I am. I’m just not someone who’s very interested in making beautiful photos—

But your photos are beautiful.

—beauty isn’t the most important thing. Of course I have my own aesthetic; I want my images to meet a certain standard. But I wouldn’t sacrifice the rest of my objectives in pursuit of that standard.

I think every photographer, at some time in their career, will arrive at this. You can only take so many beautiful pictures before, at some point, they all become really boring. They will all be sunsets, beautiful landscapes, models. What else—you know—what else? Are you satisfied with just taking beautiful pictures your whole life?

How do you judge contemporary works?

If I don’t see your artist’s statement, I would want to still understand what your idea is. If you don’t need a long essay to intellectualise what you’re trying to do, and I can see your photograph, and with just a little bit of background I can understand what you’re trying to do, and there’s a vibe, then I feel it’s a good work.

It’s not my job to shove my work in front of people. I don’t need to write an artist’s statement and repeat it to everyone I meet, because you’re not interested in it anyway, and you have better things to do.

Sometimes I think my work doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if people look at my work, because I get the most fun out of making them.

So how do you decide what to shoot?

You have to put a lot of material into your brain and then let the material slowly connect to each other. And then you can do something. What that is, I can’t articulate exactly. I just know I can’t just pull something out of thin air.

Of course, my photos aren’t very technically advanced. If you know how to make photographs, and you wanted to replicate what I’ve done, you could.

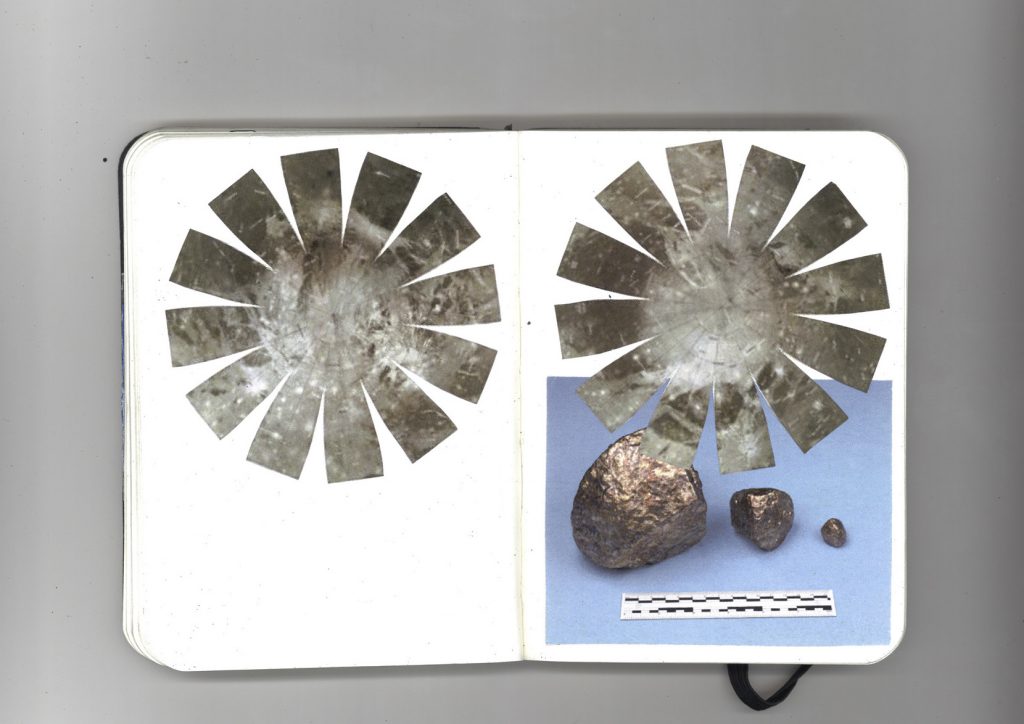

You’re working on a science photography project—tell us about it.

I was a science student. I was looking at some old science books at home—from a photographer’s perspective, I thought this was really interesting. I started looking into the history, how photography and science are so intricately linked, how photography has been an essential tool for scientists since its inception. It was evidence, because the camera can see what the human eye can’t see, it directly registers what’s in front of it.

Scientists tried hard to show the camera as “the pencil of nature.” They wanted to use the dark box to accurately register reality, as a form of evidence. Take radiation: Henri Becquerel accidentally left some photo paper out and discovered radioactivity after seeing the exposure. So that has historical weight.

But when I see what’s presented to me in science textbooks, which is ridiculous stock photos and illustrations, I don’t see that much thought put into it; it carries so little strength. So why is it like this? I was dissatisfied and I wanted to investigate this discrepancy. I find it interesting how photography used to be so important to science, but now in science education it’s so superfluous, it’s just there to fill the spaces.

So my project is about looking at the spectrum of scientific imagery, figuring out its logic and aesthetics. To study them like an entirely new system of visual language.

And what have you discovered?

I didn’t really pay much attention to science photos before I was a photographer, and now it’s almost like I understand the world deeper in a sense. I’m more conscious about my relationship with images.

You can only take so many beautiful pictures before, at some point, they all become really boring.

Every time I do a project I do a lot of research. I’ll try to understand the origins of the subject, why they came to be this way. I have a book called Revelations, and it discusses the use of photography as evidence.

There’s an example of an industrialist trying to figure out how many shoes his workers were making on an assembly line. So he asked a photographer to do a long exposure. He made two photographs to reveal the difference between skilled and unskilled workers. Unskilled workers made a lot of movements, so you could see the light trails. Skilled workers’ motions were much tighter, showing that they worked much more efficiently.

While scientists have used photography as hard evidence, people have also used photography to try and prove pseudo-scientific things. I think there’s something in the middle—like using a photograph to survey workers—and that I find interesting.

Something between a truth and a lie.

For those photographers back in the day, their work was not a lie. They were really trying to register truth onto a photographic plane—tried to reduce scientific truth and physics into a photo. But now we are in a very postmodern way of thinking about photography—how everything is staged, how everything can be Photoshopped.

I like to use photographs because they appear so real, but everything inside is constructed, everything to some degree is staged. That’s the beauty of photography—how real it looks even though you’re telling a lie.

An exhibition of Sheung Yiu’s latest project, “Look Like Science”, is on view beginning January 15, 2018 at Node Gallery in Helsinki through January 26. The opening reception is on January 19.

Interview by Wilfred Chan and Michael Chiu. Holmes Chan contributed editing. This interview is condensed and translated from Cantonese.