On Nicholas Wong’s Instagram bio, there is one line of description, two startling words in all caps: “POET RESIGNED”.

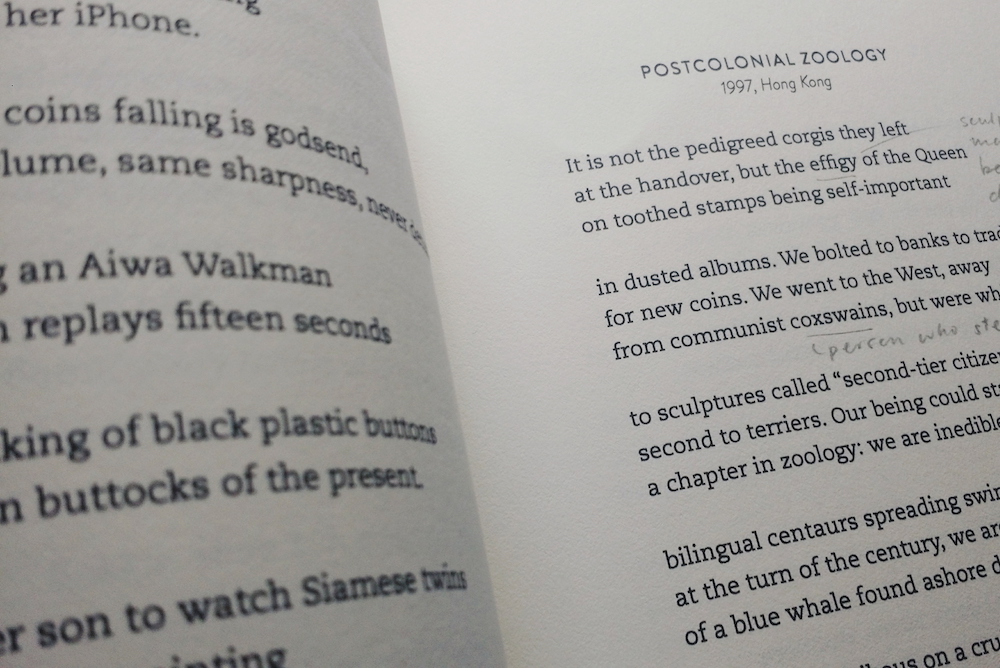

With his name ubiquitous in the literary scene, he may appear anything but. His poems were recently published in the British literary journal Wasafari and PEN’s Hong Kong 20/20 anthology. Last year, his poetry collection Crevasse won the prestigious Lambda Literary Awards for LGBTQ writing. And on November 4, Wong will be speaking at a Hong Kong International Literary Festival panel on local poetry, along with heavyweights such as Louise Ho, Chris Song and Tammy Ho.

“What I mean is that I’m a ‘poet’, but what’s fucked up is that I advertise myself as a poet more than actually writing as a poet. I’ve been a bit withdrawn, or detached, from the act of writing,” he says.

His writing slump began after the Umbrella Movement. “After 2014, the energy of the whole city changed, and so did my own. I lost my sense of balance and well-being, and I can’t write creatively anymore. The subject has overridden the entire city—it’s shattered it.”

Three years later, he is still unable to make sense of the impact the protests had on him. While the tension running through the city’s veins may motivate and inspire some writers, Wong says that he is not one of them.

“I don’t get up in the middle of the night, feeling bored, and start writing like I used to,” he says. In fact, he has barely written “anything substantial” since then; most of his recent publications are of old works.

“There are these broken pieces that don’t fit together anymore, and you don’t know how to put it together. It’s as if there’s a 20,000-piece puzzle before you, but it’s a Mark Rothko painting. So you need to try, slowly, bit by bit.”

Wong is hardly discreet about his love for the city. He grew up in the neighbourhood of Aberdeen, and has never lived outside of Hong Kong. During our hour-long phone conversation he fully demonstrated his fluency in local profanity. Last year, after he won the Lammys, he blurted out “Hong Kong add oil” in Cantonese before leaving the stage.

But in the face of the city’s political turmoil, Wong says he has considered relocating—then assured me, a rather alarmed fan, that it remains just a thought.

/

As a poet who wrote extensively about identity—his identity—Wong is no stranger to labels. With his Lammys win, he has joked about “coming out of the closet to the world”. If you type “Hong Kong gay poet” into a search engine, his name is the first to come up.

Wong has since unceremoniously assumed the role of spokesperson for queer writing in Hong Kong. He has pushed for diversity in the poetry section of the PEN anthology, which he says comprises more works by sexual minority poets than straight and cisgender ones. And even after renouncing his poetry citizenship, Wong is still an active participant of queer rights events both locally and regionally.

One of the writers featured in the anthology is Mary Jean Chan, a queer British-Hong Kong poet who has taken on a local identity in writing. “I think the label of ‘Hong Kong’ writer or poet isn’t just a geographical indication,” Wong says. “I think it’s that on some level, this location has to have given you the nutrients [for writing].”

“If we’re pushing the definition like this, I think that it can also include a lot of expatriate writing, because Hong Kong has given them the drive to write. We really shouldn’t be talking about whether something is ‘authentically’ Hong Kong anymore. We’ve been saying that for ages, and there has been no conclusion,” he adds.

As such, Wong holds an inclusive attitude towards expatriate writing, with caveats: “It is a part of English creative writing [in Hong Kong], but it cannot be the only part.”

Elsewhere, he has also expressed exasperation with the way “some Hong Kong poets write about Hong Kong.” He explains here: “Each poem should be an interaction or response to the world in a curious manner. If your curiosity only takes you to exoticising your space, then I think that’s very narrow.”

“These kinds of imagery have already been exhausted after all these years. The shoe-shining boys in Central 80 years ago and those on Chater now are the same—what’s the point of writing it when there’s no reinvention of perspective? When there’s no new angle, is there value for it to remain in the literary circle?”

Apart from being inquisitive when looking inwards, Wong also suggests venturing outwards. “You can’t just stay in your comfort zone,” he says. He thinks writers should participate in literary communities in neighbouring locations such as Singapore and Taiwan—for the simple reason that there is limited local readership in Asia, where English is not the native language in most countries.

Wong’s own work has travelled even further. Crevasse was published by Kaya Press, a U.S.-based group that focuses on diasporic writing. Wong admits that he has, in the past, attempted to please American publishers by focusing on certain themes—such as homecoming—but now dismisses those poems as “rather rubbish”.

Wong is well aware the international market is no guarantee. The current political climate limits exposure for Hong Kong and Asian writers, especially when there are enough second- and third-generation Asian writers covering similar ground. “It’s difficult for Asian politics to enter the U.S. now, because they have enough shit to deal with on their own with regard to race, sexuality and gender, immigration… They don’t have [the stomach] to digest. And when they hear ‘Hong Kong’, they’ll be turned off.”

Despite this, Wong’s story is a rare tale of success. To some, his name has become synonymous with Hong Kong poetry, and he has become an authoritative voice on what it means to write in English in Hong Kong, a postcolonial city where Anglophone writing remains marginalised and largely out-of-reach to the local Chinese population.

But Nicholas Wong, poet resigned, is starting to suspect that poetry is not Hong Kong’s genre after all.

“The Hong Kong mass seems to be more perceptive towards paragraphs. They don’t want to spend a lot of time to digest a passage… [Prose] is in the blood of Hong Kongers and in their everyday lives. Each city has their own genre, and Hong Kong needs a bit of time to explore.”

Wong says that, in the course of Hong Kong’s history, maybe Anglophone poetry is just a medium of telling stories—one among many, not so different from Cantonese song or film.

“I believe that this medium will fade out in maybe 20 or 30 years; perhaps no one will write in English anymore. And when you look back then, it’ll be a product of antiquity—and its value will be how it records the earliest days of Hong Kong when Anglophone writing first entered the city, till when it disappears.”

Nicholas Wong will be speaking at Hong Kong International Literary Festival’s 20 Years of Hong Kong Verse alongside local poets Louise Ho, Michael O’Sullivan and Chris Song, moderated by Tammy Ho Lai-Ming. Editing by Still / Loud’s Holmes Chan.