Words are dangerous. Under an authoritarian government, speaking the truth is challenging authority, and writing a book can get one charged with inciting subversion of state power — a fate that befell Chinese human rights activist Liu Xiaobo, amongst many others.

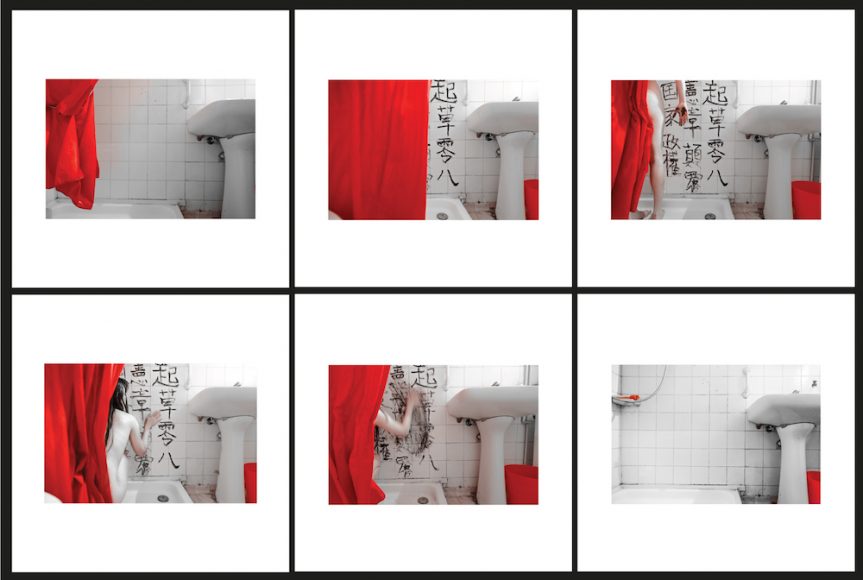

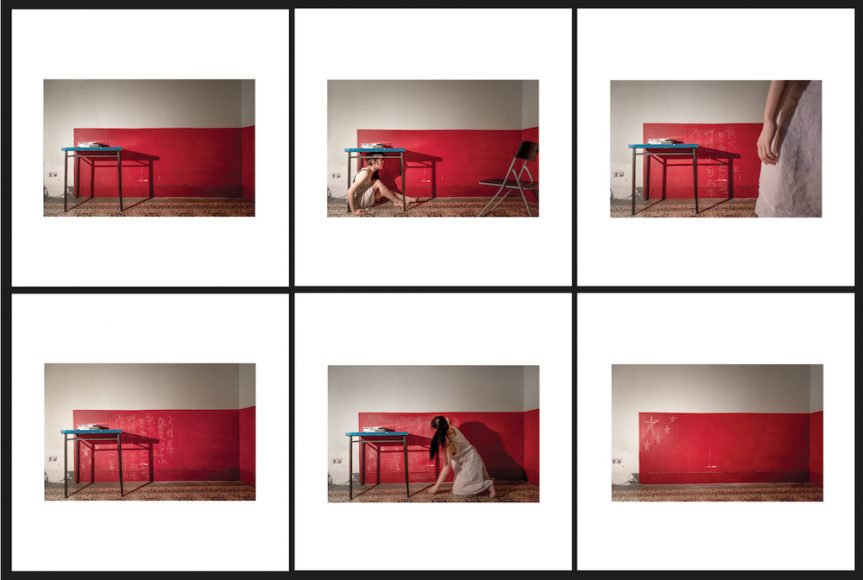

Tam Hoi-ying’s “Being Disappeared” brilliantly encapsulates the helplessness of the situation in a series of Duane Michals-esque sequential photographs. Her photos are records of performance pieces in which the artist wrote political text on bathroom walls, kitchen sinks and different surfaces. She eventually wiped out the text, leaving the scene just the same as it was from the start.

The series titled “Being Disappeared” 「被消失」 is a reference to a colloquial phrase used to describe the arrest or abduction of dissidents – a term to mock the common narrative the Chinese government puts out to mask political imprisonment as cases of missing persons. (People who are allegedly murdered by the party are reported to “be committed suicide.”「被自殺」)

/

Can you tell us about your background? Growing up, have you ever imagined being a photographic artist?

I was born and raised in Hong Kong, so I am 100% a Hong Konger. Yes, being a photographer has been one of my dreams when I was growing up but I never saw myself becoming one. With all the competition in Hong Kong and the emphasis to make a living, being a photographer/artist doesn’t seems to be a choice, practically speaking.

When did you start seeing photography as an art form/a way of expression?

This only started when I was studying photography in Spain. I used to take photos to capture moments. It was not until my experience in Spain that my horizon widened and I saw more possibilities – more possibilities in life, more possibilities in communication, more possibilities in photography. And I found it quite liberating, as I am quite an introvert. Photography allows me to speak freely in my own language.

I saw your work as a poignant response to China’s omnipotent censorship, both online and offline, enforced through the great “firewall” and the arrest of civil right lawyers. Is there any particular event that inspired this project?

Lots of the cases happened in China and they all motivated me to develop this project. If you just search a bit on the internet, it is not hard to read about human rights violation cases. It happens in every single day but not many of us are interested to understand what happened. I think the cases that motivated me the most are the ones that have been featured in my project, e.g. the case of Gao Yu, or the famous case of Liu Xiaobo… and anyone who was just trying to express their opinion towards the government or to call for justice, but ended up being captured, accused or killed.

How does your identity as a Hong Konger affect the way you see the situation in China? Do you also see threats on free speech in Hong Kong coming from the mainland?

The threat is quite obvious, but I am more concerned and feel helpless about the indifference of the majority in Hong Kong towards the violation of human rights. When we were protesting for the missing shop owners few months ago, a lot of people from the streets were accusing us of jeopardizing the stability of Hong Kong and whatnot. We just can’t expect others to hold the same value system as we do. I think a matter of right or wrong and there is no grey area in between.

What do you want your audience to take away from your work?

I really hope by questioning the meaning of communication, the format of expression, and the reason for National Security Law, people can start paying more attention to the human rights situation in China and all over the world.

There are always reasons for countries to limit the rights of their people, e.g. for protecting your safety, or to ensure social security, but what/who are they really protecting?

Text is a critical element in your work. Liu Xiaobo’s involvement in the petition campaigning for people’s political freedom has been cited in one of your work. How did you decide what to write in the photograph?

The text are from the cases that hit me hard and made me think the most. Reading about them makes me wonder if I were them, could I be as brave? Would I choose to live in silence or would I speak up? I really have doubts.

I can’t help but see a resemblance between Duane Michals’s sequences and your work “Being Disappeared.” Was he an inspiration to you? Did you plan on making these sequences from the beginning?

Yes. Duane Michals was quite an important influence for me. His methodology opened my mind to a less traditional storytelling approach. There are millions of ways to demonstrate the ideas, but to convey an internal struggle of oneself is a very complicated one. I hope my audience will be able to feel what I feel and might even allow others to join in the thinking process.

Your work is as powerful a performance art piece as a photography project — the act of writing and erasing makes a poignant statement about censorship. Would you consider doing more performative work in the future?

Performative works are quite fun to work with, though that really depends on what idea I would like to convey. I am quite interested to experimenting with different ways to communicate my ideas.

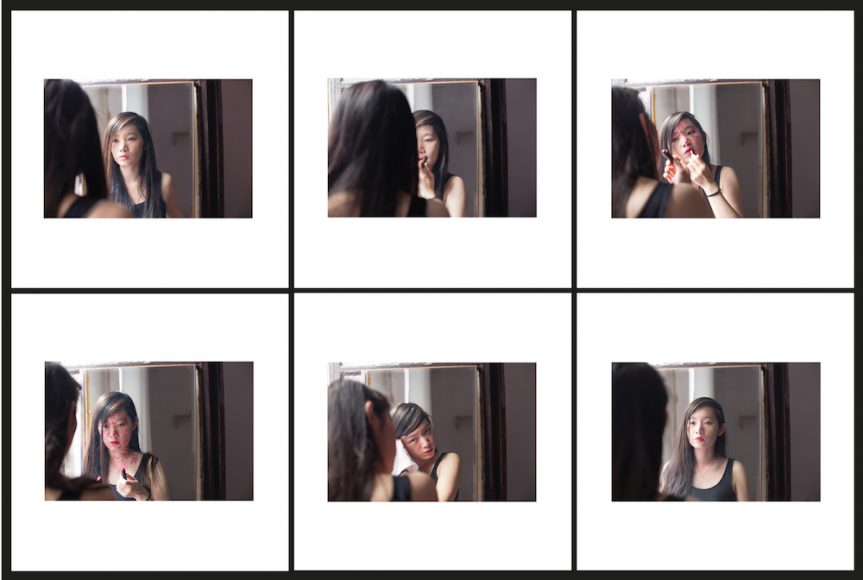

You have said in an interview with “Creative Review” that you are working on another project about social expectations that are put on women. It seems to me that social activism is a common theme of your work. In your opinion, is photography a good medium for social advocacy?

Some people dance, some people sing, sometimes it is more like it chooses you instead of you choosing it. I think all mediums can communicate social ideas, and as long as you have an idea or an issue that you would like to speak about all mediums are good mediums. For me the beauty of photography is that photographic reality fluctuates between reality and fiction. Everyone interprets the “true moment” in their own way and relate to the photograph differently.

/

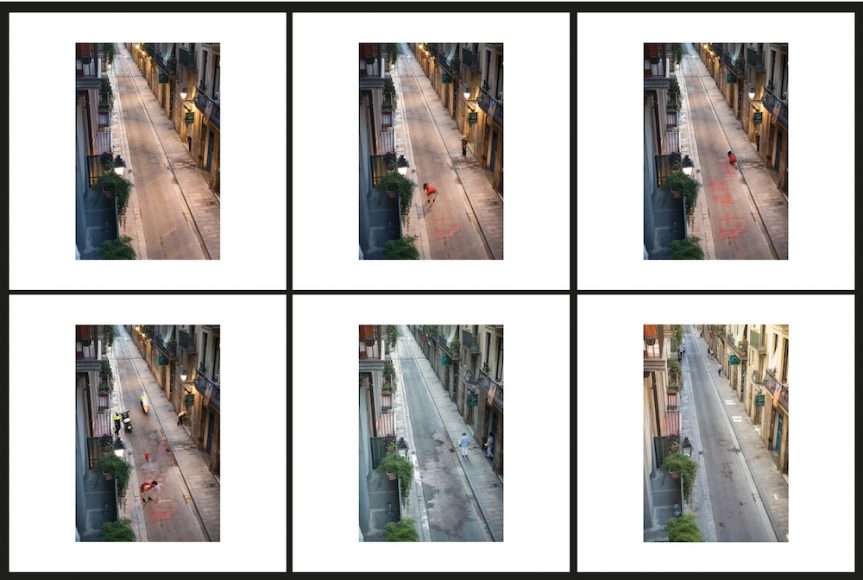

Prominent local photographer Dustin Shum once told CNN that Hong Kong’s socially conscious photography isn’t considered “as charming” as Chinese photography in the market. Yet, it is this exact same reason that makes Hong Kong photography so uniquely crucial to the Chinese-speaking community. The city, with its persistence in upholding freedom of speech, allows artists to experiment with limitless topics, making it the last refuge for political frustration and activism. Politically inspired photography isn’t necessarily less “charming” by default: Tam Hoi-ying’s “Being Disappeared” surely proves otherwise.

Adapted from an interview originally published on Invisible Photographer Asia.